A Brooklyn Timeline

DUTCH SWINDLE LAND FROM INDIGENOUS LENAPE (1626)

Previous to Dutch arrival, present-day Brooklyn, New York City, New Jersey, Eastern Pennsylvania and Delaware was inhabited by the Lenape. The region was called Lenapehoking. In a bid to colonize the region, the Dutch represented by Peter Minuit, “bought” land from the indigenous people in exchange for trinkets. However, it’s likely that the indigenous people understood the deal to be a promise to share land, rather than a sale. Today, Lenape are working to reclaim their heritage in the city contributing towards a history predating European arrival and colonization.

First enslaved Africans brought to Brooklyn (1626)

African captives built Brooklyn and New York. Brooklyn slavery was run by the Dutch West India Company (DWIC), a trading and colonizing agency comprised of Dutch merchants and assorted investors. They sailed ships to Africa and other colonies, captured enslaved African men, women, and children and forced them into labor in Brooklyn. The enslaved people created Brooklyn’s early infrastructure, developed its roads, agriculture and farms, and even protected the settlements from Native Americans. Unlike Southern slavery practices, enslaved Africans in New Amsterdam aka Brooklyn could earn meager wages and own property. The relationship could be compared to indentured servitude. In 1644, 11 DWIC enslaved Africans petitioned for their freedom after two decades of work. They were granted “conditional-freedom.” The majority of men, women, and children were taken from west and central Africa.

Dorothy Creole, one of the first black women in Brooklyn

Dorothy and the other women first brought to the colony were forced into domestic labor and sexual exploitation to bear a new generation of captives. In New Amsterdam, she married Paulo Angola, one of the first male enslaved Africans brought to the newly colonized city. Under the Dutch, marriages were recognized and documented. After 15 years working for the DWIC, Dorothy and Paulo were assigned to Dutch sea captain Jan de Fries. Creole, her husband and a number of other captives petitioned the DWIC to be freed and were granted some liberties.

Dutch invade Brooklyn, number of captives increase (1600-1643)

The Dutch expanded their colonial mission making more faulty and dishonest land deals with the indigenous Lenape. Brooklyn, with its fertile land, became the farming capital of the Dutch colony. By 1643, six villages were founded: Bushwick, Brooklyn, Flatbush, Flatlands, New Utrecht and Gravesend. The proportion of captive to slave owner in Brooklyn quickly increased with many working on farms.

Enslaved Black man sues white merchant, wins (1638)

African captive known as “Anthony the Portuguese” sues a White merchant after the latter’s dog attacks his hog. Anthony is successful in his suit and is awarded reparations. A year later, Pedro Negretto successfully sues Englishman John Seals for unpaid labor. While indentured servitude of captives was wholly involuntary, they were afforded certain rights under the Dutch. Legal disputes between captives and slave owners as well as non-slave owning White colonists were not uncommon.

“Land of Blacks” first generation captive descendant granted acres of land (1644)

Lucas Santomee, son of Pieter Santomee, a “half-freed” DWIC captive, worked as a doctor for the company treating enslaved Africans, captive and soldiers in New York. He was granted six acres of property in 1644, which included parts of Brooklyn to Greenwich Village for his medical work. Lucas’ brother and other captives of his father's generation were given pieces of land between 1643 to 1644. This area (present-day Little Italy, south of NYU) was referred to as “land of blacks” according to legal documents. Under British rule starting in March 1664, captives were quickly stripped of their former meager rights.

Dutch cede “New Amsterdam” to rival British colonizers (1644)

By the time the British seized the colony renaming it “New York” there were about 375 enslaved Africans. The British became the leading slave traders importing over 7,000 captives to the colony over a century, many of whom were sent to live in nearby rural areas. In Brooklyn, 1/3 of the population were African captives working on farms and as domestics. Under the British, the villages of Brooklyn were grouped as Kings County. Compared to the Dutch, the British were significantly more inhumane in their treatment of captives, rescinding a number of their rights.

African burial grounds (1696)

Throughout Dutch rule, there were a few sites where captive Africans could lay their dead. One major burial ground used by both white colonists and captives was located around present-day Wall Street. The land was bought by a few English men in 1696 who privatized the land and used enslaved Blacks to build the first Anglican church, which would later become Trinity Church. After acquiring the land, they banned Africans from burying their dead there. Captives resorted to using an area north of City Hall as a cemetery. After a 1991 excavation, the area underwent a period of extensive research.

Over 20,000 bodies are estimated to have been buried in the seven-acre plot, with an approximate 400 bodies exhumed. It is the largest and oldest known excavated burial site of enslaved Africans in North America. An analysis by Howard University found that many of the burials were in line with West African traditions. The historic African burial site was designated a national monument in 1993.

New York, second largest slave-owning colony (1703)

Despite historical notions of New York as a liberal bastion, in 1703 about 42% of households owned captives, making it the second largest slave-owning colony behind Charleston, South Carolina. The port of New York was a key location in the slave trade. In the 1700’s, the Wall Street and Pearl Street crossroads became the official slave market for the city hosting regular slave auctions for at least half a century.

New York Captive Revolt of 1712

On April 6, 1712, a group of African captives took arms and revolted. Over 20 set fire to property and killed slave holders. At least nine slave owners were killed, and six wounded. Some fled north of New York, but at least twenty-seven people were captured near present-day Canal Street. The majority were brutalized publicly and killed.

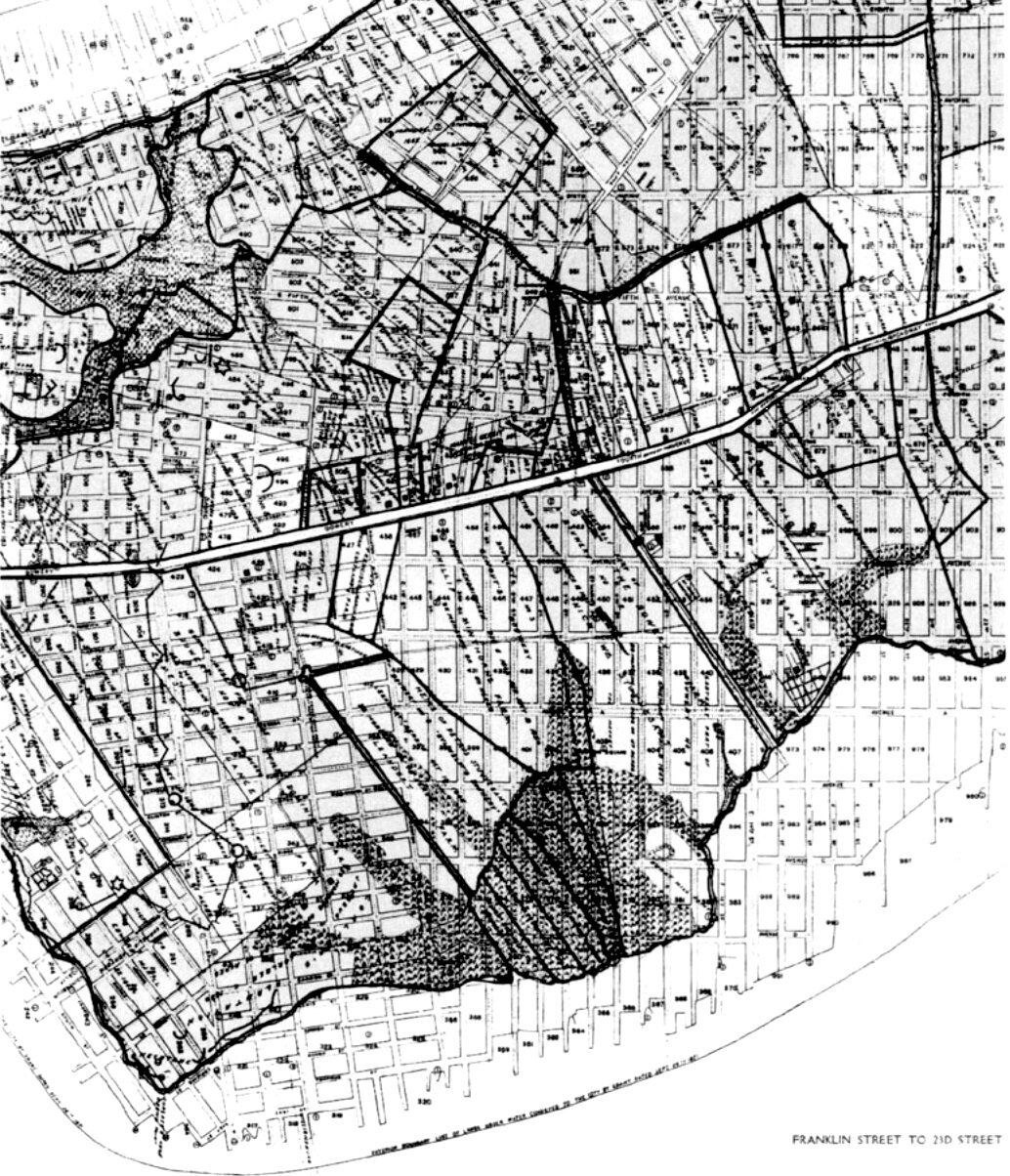

Brooklyn and Flatbush held highest number of enslaved (1738)

A 1738 census found 1 in 4 persons in Kings County to be a captive. In the town of Brooklyn of 705 inhabitants, about 158 were enslaved people. In Flatbush, 158 out of 705 persons were enslaved. By the early 1800’s, Kings County had the highest proportion of slave owners to enslaved in the North.

New York abolishes slavery (1827)

From 1799 to 1827, New York slowly outlawed slavery. Enslaved children born after July 1799 were freed after serving 25 years. As economic compensation to slave owners, this indentured servitude was introduced as a transition to freedom. Another law in 1817 passed also granting “eventual” freedom to captives born before 1799. The full legal eradication of slavery did not take place until July 4, 1827.

Free Black community forms in Newton (Elmhurst), Queens (1828)

William Hunter, a White man, deeded land to several members of the United African Society in Newton —now Elmhurst, Queens, in 1828. The community was quickly inhabited by free Blacks and enslaved Africans who built town schools and churches.

Brooklyn anti-‘Back to Africa’ meeting (1831)

A group of Black Brooklyn abolitionists including Henry C. Thompson (founder of Weeksville), George Hogarth (African Methodist Episcopal church pastor), and James W.C. Pennington (activist and minister) gathered at the African Hall on Nassau Street in response to movement started by the American Colonization Society seeking to send freed Black persons to Liberia. Thompson, Hogarth and Pennington fervently opposed the plan and demanded to be treated as equals in America.

Meet Black abolitionist, James Williams Charles Pennington (1828)

James W.C. Pennington, a minister and abolitionist escaped slavery at 19 years old in Maryland. He found refuge in Pennsylvania with Quakers where he began his education. Pennington later moved to Philadelphia then Long Island where he taught Black students. In 1828, Pennington moved to Brooklyn where he worked before heading to Yale Divinity School to study. Albeit “off the record,” he was the first Black student to attend the institution where he took classes. Pennington was not awarded a degree, nor was he afforded the same rights as his peers. Upon completion, Pennington moved back to New York where he was deeply involved as an abolitionist.

First Black-owned newspaper, bookstore (1834)

David Ruggles, abolitionist, journalist and underground railroad conductor opened a bookstore in his Lower East Side apartment. Ruggles also operated a printing press publishing anti-slavery editorials, letters and literature from his home. Ruggles’ work was widely disseminated across the country, leading to his rising prominence outside New York. In 1835, a group of White-supremacists burned his store.

New York Vigilance Committee formed (1835)

The NYVC, an interracial organization formed in November 1835 to provide legal help, food, assistance and shelter for captives escaping the South. The committees cropped up across the North with joint White participation. The NYVC intervened in over 300 cases were enslaved Africans who escaped to the North were captured by bounty hunters and brought to the South. In 1838, the NYVC with the help of David Ruggles — a prominent member— came to the legal defense of a Maryland captive Frederick Washington Bailey, who later changed his name to Frederick Douglas.

Brooklyn Blacks build Weeksville (1838)

After New York abolished slavery in 1827, Weeksville, named after Black stevedore James Week, was founded. Weeks bought the land from Henry Thompson, a land-owning free Black man. Weeksville quickly grew and became a self-sufficient community and refuge for Black Americans. Weeksville established its own schools, churches and social welfare systems. It was the second largest community of free Blacks before the civil war. By 1900, it was home to over 500 families.

Williamsburg second largest Black community (1840’s-1850’s)

Behind Weeksville, Williamsburg was the second largest black community in Brooklyn and fostered abolitionist activity. William and Willis Hodges, free black men from Virginia settled in the neighborhood and worked on the Ram’s Horn, a weekly abolitionist publication funded by Fredrick Douglas amongst other leading figures.

Free Black man seized, then liberated (1850)

James Hamlet, a free Black resident of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg, was taken by bounty hunters and sent to the South. William Powell, member of the New York African Society Mutual Relief, represented Hamlet in his return to New York. Powell organized a march on City Hall, mobilized the community and spoke to authorities to secure Hamlet’s safe return. In a matter of weeks, Hamlet was escorted by hundreds of free Black people back to his Williamsburg home.

Meet Elizabeth Gloucester, the richest Black woman of the 19th century (1855)

Elizabeth Gloucester, born in 1817 Richmond, Virginia, to a freed woman. After her mother died young, Elizabeth was sent to live with Rev. Dr. James Gloucester, an abolitionist, who founded the first African American Presbyterian Church. After marrying one of his sons, Elizabeth moved to New York, sold second-hand clothing and ran a furniture store. She and her husband later founded a church in Brooklyn. In the following years, the couple had amassed a number of properties, which Elizabeth ran as boarding houses. The wealthy and successful couple deeply invested themselves in the abolition movement.

Brooklyn streets named after slave traders (1860’s)

Find your Brooklyn street on this list. Major slave traders and colonizers Peter Stuyvesant (Dutch) and the Schermerhorn family (Dutch) are commemorated by street names, housing developments and neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Stuyvesant, the Directer General of “New Netherlands” expanded slave trade in the colony becoming the largest private owner of enslaved Africans in the new colony. The Schermerhorns were major investors in the slave trade and conducted trade between New York City and Charleston, South Carolina.